| The Night Land |

| Night Scapes |

| Night Thoughts |

| Night Lands |

| Night Times |

| Night Voices |

| Night Maps |

| view guestbook |

| sign guestbook |

| blog |

By John C Wright Part 4

28. THE LAST OF THE FIRST FOLKI said, "It was you. You opened the coffins in the archive, to create the distraction, and you sent Nergal to fight the overseer." He said, "I opened but one coffin: your own. You produced the rest, all the millions of men, from your mind, because the solitude had driven you mad.” “Do you mean I hallucinated them, or do you mean I rotated them into flesh using Abraxander’s dimensional mind-science?” “What does it matter, after-man? Even now, does sanity matter to you?” “Your voice has changed,” I said, “Your way of speech. What language is this? Who are you?” “This is the Tongue-before-tongue, the proto-language known to all men. You know me. I follow you through all your changes from life to life, so that I may be with you at the end of all.” “So you came here. You stirred up the rebellion in the Archive to free me. None of the other men, only me?” “Fool. There was no rebellion, no giants to fight. Those lesser servants of the darkness were long ago consumed by the greater servants. We have run, you and I, down empty corridors of a dark, deserted ship, for weeks, and months, and years, and decades, with no one and nothing in pursuit. I watched while you fought battles with invisible foes, wept over imaginary comrades fallen in battle, and fired pretended weapons at fictional monsters." I straightened up. In a voice of relief, I said, "Then, if I am merely mad, and those nightmares merely from my own mind … Thank God!" "The hounds and Mantichores are imaginary, the behemoths, the giants and the Great Gray Hag. But-“ He tilted his head and grinned. “No!” “But the Silent Ones are real. The Watchers are waiting on every deck of this vast ship, and watching you, the last of all the sons of Man." “Not the last. Mr. Singer, Mr. Bliss, Ydmos, and the others-“ “Shadows of you. I don’t know why you conjured them. Perhaps you meant them to argue your decisions for you: the faithful and the faithless, the wise and the impulsive, the noble and the humble. As Mneseus, you tried to convince yourself to kill yourself; as Enoch, you prevented it.” "No. Surely, I am merely hallucinating all this …" "Until today. Your imaginary weapon went off. I heard the report. I saw the bullet-hole appear in the far bulkhead. I smelled the smoke, and heard the spent shell-case tinkle on the deck. The distinctions between is and is not, was and shall-be grew thin, as time wore out. I knew, after centuries of following you from life to life, the time to consummate our agreement had come: and so I brought you here, where you were allowed to view the Last of All Suns, where all the ghosts of all the dead worlds of creation are gathered to their cremation. Now the ghosts will board the ship, attracted by your affections." “Agreement? What agreement?” “I am eldest. Death is not amnesia to one of my race, nor do we forget our dreams on waking. Each life, I find you and remind you who you are, and tell you if the woman has been reborn, so that you know to seek her. Our agreement: you have your woman, over many lives, and you promised that I should have mine, finally, once all the stars have died. All we need do is allow them to corrupt and poison the new creation." "What if I kill you now?" He snorted. "Strike! I will live again, and in less then a minute. It will halt nothing. Abraxander saw me do my work, and he did not stop me. Now, my part is done: I have brought the world I remember within hailing distance. I call the ghosts. Now the ghosts call you.” Unthinkingly, I put my hand down to pet the dog I found at my side. His fur was long and golden, and with a rough tongue, he licked my hand. "Pepper?" I asked in confusion. Pepper barked and wagged his tail. Then he sniffed the Neanderthal, and he growled, and hunkered down. I said, "Did they promise you your mate again, if you betrayed us?" He shook his shaggy head slowly. "Not me. You. You are the one who made the promise to them, long ago, in another life. You are the one who carries the coal from which the new universe is meant to catch fire. I am merely here to breathe on the coal." I said, "What coal?" He said, "Love." "Love?" He snorted at my ignorance. "Fool! Of what else could a universe be made?" I said, "Why do they want a new universe made? These monsters? What do they want?" "They want to eat it again." “Am I going to make the universe, all by myself? I am no god.” “You are a dove Noah sends out. They want to find the new universe.” I had to laugh. “The universe is a pretty big place. How can they miss it?” He said, “At the moment, the cosmos is sub-microscopic, smaller than the diameter of the core of an atom. Somewhere in here, in the Central Sun. The cosmos is yet a seed. If they find it after it starts to grow, too late for them to enter. You will lead them to it. They cannot find it without you, without human life.” “You won’t do? You are alive.” “I am Noah’s raven. I was sent and failed.” “Failed why?” He shook his head, but would not answer. I said, "Suppose I do find this new universe, smaller than an atom. Why would I tell them? And how could I even see it?” He shook his head, but drew back his teeth, a grimace of assumed contempt, as if I had said something childish, unutterably foolish. I asked again: “And what if I defy them? What if I simply say no?" “The worm needs do nothing on the hook but twist.” He pointed at my hand. “Look to this weapon. You were merely fond of it, familiar with it. It is nothing. Your woman, your people, those you love. They are everything. The sun and moon and stars. The wilderness, the sea. The House of Silence found a man like you, a wanderer, who would know many lands and love them. That love, by itself, will seek the place where all these things can be made again, even as a magnet seeks a magnet. They would not let me tell you anything that could hinder their terrible purposes.” “Do you speak to them?” “No. I hear whispers in the night, in my soul, and I guess at their desires. But I still live, as do you. They spare me. If not for this, than what? We are within the last few breaths of the End Of Time, and short breaths, too: the cosmos has less than a moment to run. I can sense the Omega Point is near. Look outside! The bubbles, the faces, the ghosts: all is gathered into one pinpoint of infinite light. In a moment, the light will vanish, as all reality eats itself.” The golden light winked out, but there was still a dull reddish glow, like the glow from an iron forge, filling the last few cubic miles of the shrinking universe. “What are those dark walls I see? They are above and below and all around.” “The hull of this ship.” Underfoot, through the porthole where I stood, I saw what I assumed was the dark skin of another ship, but as if that ship were turned inside-out, and wrapped around the ship where we were, with a hollow space between. The memory of Abraxander showed me what a flat, two-dimensional man embedded in the surface of a shrinking balloon would see, if he looked to any side of him. The flat, two-dimensional waves of light reaching his eye would follow the curve of the balloon, from west to east all the way around the equator to strike his body from the other side. But, to him, the balloon would seem a flat and level surface, and so he would see his own body, as if turned inside out, forming a boundary around the edge. As the balloon shrank, each point of his inside-out two-dimensional body would press inward, and the edge grow ever closer, till he was staring himself eye-to-eye, almost kissing his screaming mouth. So, in three dimensions, was this space around the ship, filled with nothing but a distorted and reversed image of itself, as if trapped in a ping-pong ball, whose inner curve was all a mirror. There was no way out. The universe was as if held within a hollow ball of metal. The iron walls shrank in and grew closer. I saw that the hull was crusted as if with barnacles with gargoyles: hulking shapes as big as mountains on a sterile plain of endless pock-marked metal. They had faces; they had eyes. I could not breathe, for claustrophobic panic seized me. Pepper whined and barked. I drew a safety match from my pocket, and struck it on the metal barrel of my gun. The tiny, tiny fire in my hand was the only source of light in the universe. Directly opposite me, directly underfoot, as this hull-wall drawing closer, and in the midst of the rings of mountains-sized sphinxes, was the tiniest imaginable dot of light. There was one porthole, one window, out of all the endless miles of that dark hull, endless rows of blind windows, where the tiniest imaginable man, as if seen from below, hovered with his feet toward me, and held a spark in his fingertip. I saw myself from across the universe, mirror-reverse. I realized that the universe was now so small that images were circling the diameter of the cosmos to touch my eye. At the feet of the mountainous sphinxes and huge, inhuman faces, little thin shapes stood, draped in fabric, hooded and veiled. They must have been as tall as trees, for me to see them at this distance, but my soul was struck with chill to see them, for all the hooded shapes were bent toward that one porthole, watching that one spark. “What if I put her from my mind? What if I simply stop dwelling on her, or on the world I have lost? What if I--” The words were too absurd even to say them aloud. What if I, by an act of will, forced myself stop loving everything I loved? What if I merely made myself empty inside by wishing it so? Uj chuckled sardonically. He did not even bother to mock me. I could not bear to see the look of dark, sardonic triumph on his wolfish, brutal face. I threw the match down. The universe went dark. I blinked. It was not utterly dark. In the middle of that darkness, from one, unimaginably tiny, unthinkably distant, (and yet, somehow, inexpressibly close) point of perfect golden light, something reached out. And a curtain of flaming light came up from the dark glass surface where I stood, and in the middle of the light was a bright shadow. The shadow was curved and slender, a woman's shape, and I saw the eyes and lips that I adored, the hair brighter than gold, and she lifted her small, well-shaped hands toward me. It was Lisa. I could not help but step forward. I could not have stopped myself, not even to save the universe. We embraced. Warmth was all around me. I woke.

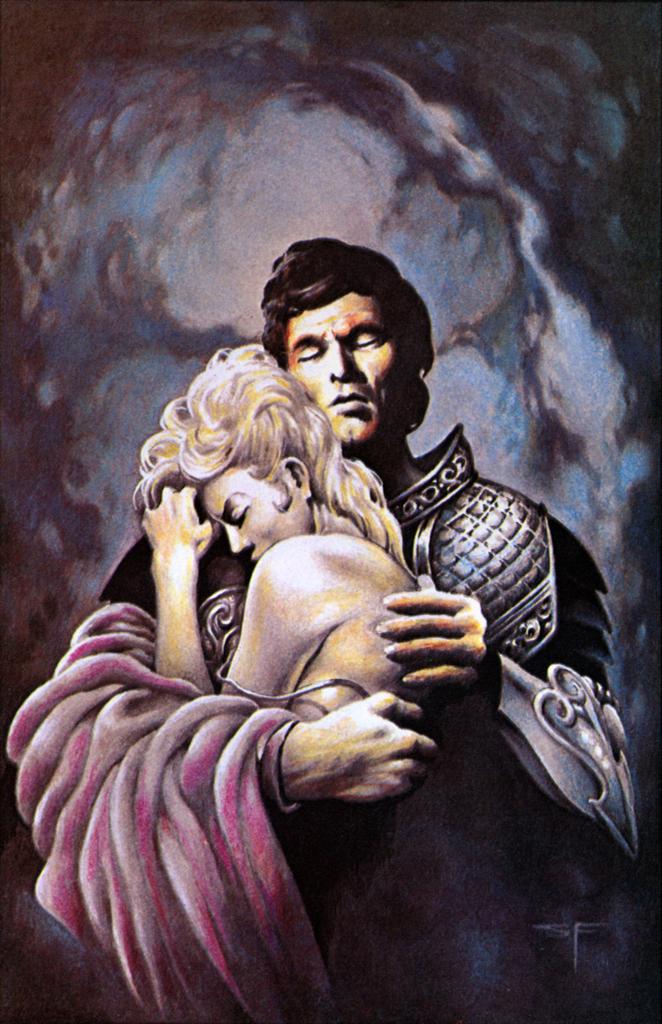

29. IN THE TENTI was laying on a canvass cot, dressed in no more than a shirt. To one side of me, a camp-stool with square wooden legs served as my night-stand: here was a thermometer of red mercury, a shaving glass, a small tin box with a red cross on it; the first aid kit. A little stoppered bottle of medicine, with a syringe, was to the left. My hip-flask, filled with some devilishly potent stuff I got from the Arab at the depot, was to the right. For a teetotaler, Rahim knew where to find better than the bathtub gin we drank back in the states. I swung my feet to the floor, and was dazed for a moment, weak. Beneath my feet was the skin of the tiger I had shot in Bengal, nicely skinned, and the skull dressed with amber chips for eyes. Beneath the rug, was golden grass, and tiny, reddish clods of dusty-smelling soil were visible between the brown roots of the tufts of grass. A haze of dust hung in the hot air inside the tent, giving it an air of unreality. I grimaced. An air of unreality was not entirely inappropriate, things being as they were. From the roofpole of the tent, hung my canteen, shining metal held in a pocket of green canvass. My leather ammo belt and hunting jacket also were nearby, hung up neatly, but of my rifle, there was no sight. This was not a good sign. One keeps the arms of a feverish man away from him. Through the open tent flap, I could see a wonder. If you have never beheld Africa, you have never seen clear skies. Nothing in New England is like it. The sky was like hammered pewter in the distance: the sun, a monarch of fire. The hills and swales of sun-baked grass were gold and tawny, the hue of a lion’s mane. In the middle distance, a line of thin, dark, crooked trees marked the wadi where the river would run, when the rains came. The plains are wide and wild and large in a fashion no poor soul in Boston will ever see. Many New Englanders understand the romance of the ocean, of far horizons: but this place, as unbound and as mysterious, few understand. I brushed off my shirt: there were dog hairs all over it. From Pepper. That was strange: but, on the other hand, Lisa’s father was an odd sort of duck, and might think it was medically a wise practice to let a man’s dog slobber in his face when he was sick. A slender shadow fell across the tent. She was there. My wife was framed in the triangle of blazing brilliance behind her, the breathless shadows of the tend folds to either side. My eyes could barely focus on her, because of the gloom where I was in the tent, the brightness where she was, and it looked almost as if she were standing at the far side of a tunnel. Her eyes are a blue as cornflowers, and her hair is gold, and her skin is bronzed and lightly freckled from her days in the sun with me, the nights beneath the tropic stars. She wore riding pants and boots, and a gun-belt cinched her narrow waist. The starched white blouse enclosed her curves in military lines. She wore a pith helmet with a scarf floating down her back. I rose and opened my arms and stepped forward …. And she put up her hand and giggled. I looked down. There I was in my underwear. She said in her lilting accent, “Ach, don’t worry it, mine Liebchen. We are man and wife now, yes? On the honeymoon, I am supposed to see your hairy knees. Such hair you have, and everywhere! This is the worse of the ‘for better and worse’, yes?” Then I did grab her, and I did kiss her. Sobbing, I held on to her, and told her how I had missed her. My words were mumbled, pointless, trite. She was overcome by them nonetheless, and melted into my arms. I took her lips forcefully enough to dip her back over my arm, a graceful as a waltzing maid, she bowed back, submitting, her arms curling my neck. I could feel, like steel beneath the velvet, the lithe muscles of her slender frame. No, she is not an indoor-girl, my Lisa. One moment, she was shivering from the sob she was trying to keep in. “I thought I had lost you, lost you!” she said. But the next, she was cool and playful, nibbling my ear, and whispering, “Ach, and this is the better, yes? Let Mrs. Powell up for air, Mr. Powell.” I put my hands on her slim shoulders and pulled her upright. “Anything you say, Mrs. Powell.” Her helmet was in her hand (she had doffed it during the kiss) and now she raised it as if to don it again, but then stepped into the tent, mopped her brow with the scarf, and dropped the helmet on the cot. “Is too hot in here, Meister Powell, nien? If you are better feeling, put on the trousers, and let us find a cool spot. You can teach me how to wrestle, like you promise back in Marakeech.” She favored me with her little impish twinkle, and took the pack of cigarettes out of the pocket of my jacket, which was hanging from a tent-peg. Casually she tossed the pack to me, and sat herself on the edge of the cot, her small hands griping the wooden slat to either side, her booted legs crossed, her shouldered slightly shrugged, her head held in a relaxed poise. Her eyes were half lidded as she watched me, and a little sensuous smile could not help but creep into her lips. I drew out two cigarettes, put them both in my mouth, lit them with a safety match, drew, and plucked one from my lips and offered it to her. She rose languidly, swayed over to me, paused to examine me a moment, and, with the slightest curtsey (for Lisa is a tall woman) she bowed her head a bit, taking the cigarette from between my fingers with her lips without touching it with her hands. Now she leaned back, drawing thoughtfully, and she blew smoke toward the tent roof. She stood with one hip cocked, her arm half-folded, cigarette dangling from slim fingers, her head tilted to one side. “I think, to be married to you, Meister Powell, I am going to be liking this verr-rr-ry much, yes? Oh, yes.” And she could not hide her smile. I said, “This is a dream.” Her smile widened. “Oh, a dream it is, my love, yes.” She tossed back her head and shrugged. “Every bride, is she as happy as I am? I do not believe it. The world could not stay together, if there was so much happiness, so much, in the world. It would burst into pieces!” “No, I mean this is really a dream. It is not happening. It is taken from life, but it is not life. I was in this tent before, but it was when we first met….I fell ill after drinking bad water. Your father was the nearest white man, and my guides brought me to him. Everyone had heard about the beautiful blonde valkyrie, his daughter, he had brought back with him from Potsdam, but I had yet to set eyes on you. “While I was ill, I had strange dreams then, that I was trapped on a ship circling the last of all suns, while brooding faces with staring eyes, or faceless things in hoods, all waited for me to let them and their hellish crew back into the universe again. I stood at the threshold with a strange axe in my hand, killing pig-things, and…. “Well, I was delirious for a long, long time. “You were my nurse. You brought me back from the brink of death. I woke from my nightmares and met you. “You did not walk in on me naked when we first met: but that did happen during our honeymoon. I did not even know I was in love, at first. You were just my friend’s daughter, a woman who liked the wild, a woman who knew how to ride and hunt and shoot drink whisky and smoke tobacco. “For so many weeks, we were just friends, you and I, friends like man-friends, if you know what I mean, like you were just one of the boys. We told each other everything, including the kind of things a man doesn’t normally tell a woman. “Mother was wife-hunting for me, when I was back in the states. I asked you to pretend to be my fiancée when I went to visit home, to get Mom off my back. The joke turned real before I knew it. It took me quite a while to smarten up, get on my knee, and give you a ring.” She smiled at that.

30. LISAShe said “A long time, yes, too long. But I knew I had you snared when you agreed to take me to see your mama.” I said with surprise. “I never knew that! You did that on purpose?” She chuckled warmly. “Do not underestimate the superior mind.” “But it was just a joke I was playing on my Mother.” “To you. Women do not joke about such things,” she said primly. “Oh, come now. It was my idea to…” “Ta-ra-ra.” She snapped her fingers. “I pick to marry you, so it is done, but I am patient, as the huntress in the wood is patient, for you to come to your senses, and ask.” I said slowly: “I never knew that when I was alive. That means this scene, this dream, cannot be just from my memory.” I gestured to the right and left. “This is from when we first met. But your little speech about seeing me naked, my hairy legs, that was when you surprised me in the binnacle. We were aboard my cousin’s schooner for our honeymoon, touring the Aegean, seeing the Greek Islands. Strange. The monsters, well, they somehow must have confused or combined elements from the two happiest periods in my life. But it never happened this way, not while I was alive.” “What-what do you mean?” “I am dead, my dear. I think you are pregnant when I marched off to war, because you were so moody. I actually had your letter in my hand, and had lit a match to read it, when a sniper saw my light and shot me. Took me about an hour to bleed to death. Stupid of me. I won’t do that again. Never did find out what was in that letter. I hope it was good news.” She raised an eyebrow at that, and puffed a nervous little puff. “Ah! What is this you say? Never mind it! Listen: Little ones; how many children do you think we will haff? I am strong; you have good bones. How many?” I said, “Seven. Four sons, three girls.” She smiled at that, and her eyes danced. “Seven? This is not bad. No so many as Mama, but-“ she shrugged. “I am the modern woman now, yes? American.” “Two of the boys will grow up strong and tall; one of them dies in the crib. The girls will be as beautiful as their mother." I heaved a sigh. “Our eldest boy will be called Frederick, after your grandfather. When he is fourteen, he will be the man of the house, and yours sons will comfort you, once I am … gone … you will still be young, with children between six and sixteen, and your folks will urge you to remarry. Long you will live, my love, long enough to see a man step onto the Moon. Frederick will die in another war. Joseph will carry on the family name.” Her eyes narrowed, and the gleaming love-joy in her eyes was muted. Another puff of the cigarette: this one rapid, nervous. “This joke you are making, I do not like it. Die in crib? Gott! That you should say such a thing! War? What war?” “Two wars. I die in the first, Frederick in the second. Germany will re-arm. Pacifists will weaken the will of the West to resist, and England will be slow to cry foul. A terrible war. A war fought with scientific weapons. Flying machines. Poison gas. Rapid-firing guns; cannon with rifled barrels. There will be an armistice for ten years, and then the Germans will attack again, and the Japanese will help them. There will be Ironclads and land ironclads. Rockets. Planes made of steel. A wireless method for detecting ships at sea. Bombs that turn whole cities into ash.” She tilted her head to one side. “Lay down. You have been sick. You must wake up from this.” I sat on the bed and she passed me the hip-flask. “Drink! You will feel better.” It burned my throat, but turned into a pleasant warmth in my chest and belly. I said, “I have stepped outside of time, and the devils want to use me to re-create all the misery in the universe. If I let them. I am the last life-line, the last thread, stretching between-I don’t know what to call it-heaven and hell, I guess. The devils want to use me to call back the things I love. You. Your family through you, and mine through me, I suppose. You could get all the generations of man back to the beginning, that way, I suppose, because no one was never loved by no one: every baby had a mother some time. And-“ She said sharply, “Let us hear no more of this talk! You, you make yourself sick again, you are, yes?” Angrily she threw down the cigarette butt and stamped it under her toe. So many things about her are so perfect. The line of her thigh when she lifted her leg to step, the black and shining gleam on the toe of her boot. Such a little foot, so pretty. The flash in her eye, blue as summer skies, when she tossed back her head and blew from her red lips upwards, to dislodge some fine strand that had escaped her tight coif to tickle her nose. Everything she did was comical, and sweet, and solemn, and dainty, and fierce, and, oh, so very feminine. I said, “This is a dream. All the details are wrong. Look.” I plucked the dog-hair off my shirt. “I did not get Pepper until four years after we were married. How can his hair be on my shirt? This is the camp where I first met you, but you are talking and acting as you did on our wedding night, which we spent, if you recall, on my schooner, sailing the Aegean.” I looked back and forth. “All the details are right. Little things. My tiger-rug. But I never would have used it for a ground-cloth. And the amber beads my taxidermist used for the eyes: I bought them in the queer little market in Cairo. I have not been to Cairo yet. But I loved that rug, and it did feature prominently on my honeymoon.” She looked at the dog-hair, and at the rug, a vertical crease of annoyance between her pale eyebrows. Then she giggled at the rug, and smiled her wicked little smile, hiding it unsuccessfully behind her fingers. I said sadly, “Naughty girl, thinking about the honeymoon uses of a tiger-skin rug at a time like this. And, yes, that is why it becomes one of my favorite rugs.” “Very well!” she said, growing sober, and she put on her face what I like to call ‘her Prussian face’, which she would use in years to come when she was trying to explain to our children, why it was illogical to cry, or why it was important to stand up to schoolyard bullies, even when very afraid. “Let us be scientific about this, yes? You say this is a dream. What dream?” “It is the moment of time between the destruction of the old universe, and the beginning of the new one. It may be too late already, but something must be happening now, right now, to set things so that the new universe is created as one They also own.” “So, then,” she shrugged, “You wake up, new universe starts, all is happy, yes? We go back to the honeymoon. I want to start on the seven little ones. Will be a lot of work.” How could I help but smile? It brought tears to my eyes, to see her again. But it was strange to see her so young! So thin! I had to hide my eyes in my hand, so that she would not see my tears. “You are in pain? I will get mine father.” “Wait,” I said. “Let us be scientific about this. The devils-I don’t know what to call them. They are not from inside the universe-want to use me, want to use my love for you, to do what? Uj would know. Something bad. Mr. Bliss spoke of orchestrating the moment of creation, running it like it was an adding machine to sum up to what he wanted. Mr. Threshold said we could use his art, the dimensional rotation, to move ideas from the realm of memory into the material realm, folding something along the time-axis back into three dimensional space, fleshed from dreams. But I am bringing the enemy in with me. What is the word? The enemy was ‘entangled’ with my former lives. Enoch was the one who did it. He is part of me. So everything I do is somehow tainted or poisoned.” She started to move away. “Father will help you…” I held up the hair from my coat again. “Whose dog is this?” She said. “Pepper. He leaves the hair over everything. You know that.” “Where is Pepper now?” “With your mother, at her house, back in Nantucket.” “Across the Ocean. Then how can his hair be here? How can I do-this?” Since imagination, like everything else, was part of the indistinct totality, I needed do no more than imagine the thousand-sided nine-dimensional hypersolid, anchored it in the points that Abraxander’s people had prepared to receive it, and the imaginary object would move the ideal object, which, in turn, since time is an Idea, would affect the time-versions of the object. And time, after all, was merely one aspect of space, so to move one was to move the other: a slight pressure was all that was needed to move from the fourth to the third dimension. A link led from the hair, along the time-axis, the to source of the hair. And of course I love my dog. So, I squinted, and- There came a bark echoing in the distance, faint as a dream, like the wind. Then paws were rustling through the grass of the plains. A wraithlike Pepper bounded into the tent. So happy I was to see him, that, in less than an eyeblink, he his bark took on texture, and his body cast a shadow. There he was: loud, sloppy, solid, and needing a flea-bath. He stank. I petted him and made much ado over him while Lisa, showing great aplomb, helped herself to a slug from the hip-flask. She coughed and sneezed only a little. She said, “Enough. Proof is proof. I believe.” “Then help me?” “How? This means I am not real, either, you know.” I blinked at that. “I - I suppose. Are you an image in my mind, or-a ghost?" She shook her head brusquely, her Prussian look back on her finely sculpted features. “An image of something to come. A temptation? Maybe I am a promise. No matter. I will help. What am I to do, eh?” “You must help me to commit suicide.” I passed my left hand over my right forearm. Again, I saw the multi-dimensional geometric shape in my minds eye. Again, I turned it. Ydmos was myself, reincarnated into the future. Surely no man has ever lived, who does not love himself, with some part of his heart, in some way. When I drew my hand back, I saw the raised red spot on my forearm where the Capsule was embedded. The Capsule is made so that the venom is released both into the mouth, and into the big veins near the elbow, when the traveler despairs of ever returning to the Last Redoubt as a human, and bites it.

31. SUICIDEShe put her little hand over the reddish mark on my arm. “No,” she said. “That is madness, cowardice.” I said, “Not cowardice. Not when done for reasons such as these. The Romans often slew themselves when…” She just gave a snort of contempt. “Romans, eh? Italians, but old, that is all.” “They were brave and great men: Trajan; Cato; Aeneas; Seneca…” “The pagan, he martyrs himself to serve his own glory, no? And on the inside, he worships himself. Just himself, nothing else. Very small thing, a man; not a worthy thing to be martyred to, I think.” “Japanese Samurai, when his honor has been…” She just rolled her eyes at that. “Honor! Another word for man who talks big, too scared to back down when people are watching. Universe is dead, you say. No one watching now.” I drew back from her. “You think it is a sin, don’t you? A mortal sin.” She narrowed her eyes and looked at me closely. She said, “I know you, Reginald. Your father, he believe in nothing, he like to go fishing on Sundays, so he let you skip church. Then you listen to college boys, and you decide to be the fool, in his heart, who says there is no God, eh? Fine. Maybe there is, maybe there is not. Many men, many brave good men, believe this thing, many years. My father, he believe so much, he goes to all countries, places that mean nothing to anyone we know, and he feed the poor and help the sick. He believes the story. But suppose it is a lie. Why is it so convincing? Why so many men believe this lie, all these years? Good men and wise. Every country, even pagans, some sort of heaven, some sort of God.” I said, “It is not hard to explain. All men fear death. All men regret that there is no justice in the world. All men are horrified to imagine that this, all of life, is an empty abyss. So they invent a story to make it all make sense.” This sounded so much like the words of Crystals-of-Bliss. He, too, had been another incarnation of mine, hadn’t he? She pursed her lips. “So. This story, if men were cowardly little things, they would have a cowardly little story, yes? If the story tells you, ‘Man, he is too fine a thing, like an angel, a thing like fire, divine fire, he is too fine for you to kill him’ that is not a little story. That is big story, yes? What kind of man listen to that kind of story? Big man.” She reached and pulled the cigarette from my fingers to take a puff. Her left hand was gripping her right elbow, and her right hand was near her face. Her hips were cocked to one side in a relaxed posture. She seemed so golden, like a cornstalk, so supple, like a steel epee, and the smoke drifted above her, catching stray rays of sunlight that pierced the stitching in the tent, and turning to golden motes. Lisa continued: “Maybe story is not true, maybe it is. I think about that later.” She shrugged. “But this story, it tells you life is good, life is sacred, then it is not a bad story, no? Because a good story, it gives you the heart to do the right thing when the wrong thing seems wise and brave. So?” I shook my head. There was no point in trying to explain things to a woman, even a woman as Amazonian as Lisa. I said, “There are things more sacred than one’s own life. Ask any soldier.” “It is an insult to all that lives, you know.” I said, “What is?” “To kill yourself. You are saying to the bird: Sing no more to me. You are saying to the sun: Shine no more on me. You are saying to the tree: I need no shade of you, do not stand. No drink from the stream, no twinkle from the star, no smile from a human face, no bark from the dog who is loyal. To everything, you say: I hate you.” I rose to my feet. “But this is a dream. I am being shown what I am about to lose. The birds and suns and stars, everything we thought eternal, it is all gone.” She jabbed the cigarette toward me an in angry gesture. “Then what is worth fighting for, eh? You are alone in the universe. Everyone dead. Nothing is real. No one is watching. What is worth fighting for? What is worth dying for?” I squinted at her. “So tell me.” She sniffed. “Same as before. Same things as when you were alive. You remember you are a man, yes? You know what it means to be a man?” I opened my mouth to answer her, but the dream faded. Lisa evaporated like cigarette smoke. The warm African sun, the savage and beautiful golden plains; it all vanished.

32. THE PLAIN OF SILENCEIt seemed to me I hovered in the void, above a vast, limitless, plain. All was drenched in a sullen reddish light, as if from the coal of a dying fire. Nothing on earth could be so large as that: the plain had no end. The horizon was so wide that it formed the equator of the globe of my vision: I suffered the unpleasant optical illusion that the ground was curving up around me, a hemisphere. But the sheer size was staggering. Directly underfoot were craters and mountains, as might be seen from a low-flying aeroplane; halfway to the horizon, were smudges and textures, as the mountains of the moon might seem seen from Earth, without a telescope. Three-quarters of the way, the texture was a misty wrinkled redness, as far off as the nearer constellations might be; and again, the horizon was even farther than that. It was as large and far-off as the sky of the winter midnight, if the sky were filled, not with star-pricked blackness, but a level expanse of stone and rock the color of old blood. Above me was a black circle, vast as the sun, and from the edges of this disk were arms of fire. It looked like an eclipse, or perhaps as if the a dead sun, his mighty sphere dark, had yet some faint fire left in his atmosphere, visible when seen in profile, at the rim of the disk, invisible when seen straight on, at the center. Directly below the dead sun was an impact-crater, marring the flat perfection of the ruby plain. As I dropped my gaze, my point of view dropped. Swift as a falcon stooping, I was thrown down through miles of air into the crater. The crater was larger than the Earth. A planet the size of Jupiter, falling, could have made such a place. The debris thrown up from the crater was taller than mountains to each side. The Himalayas, Mt. Everest itself, would have been less than a foothill, compare to these terrible slopes. The peaks were hundreds of miles high. So deep was the crater, that, even at my speeds, many minutes passed before the floor came into view: a land larger than Texas, made all of cracks and canyons, pock-marks from lesser craters, long-cold lava-flows, dead volcanoes, hills of ash and soot. It was a sterile world of lifelessness. No drop of water, no blade of grass, no midge, no mite, no smallest thing was here. Except, suddenly, in the middle of the crater floor, rising atop a lonely peak, was a house of greenish jade. It was a strange and massive house, built of cyclopean blocks, like the Great Wall of China, or the circle at Stonehenge. The house was circular in form, and had three stories, with walls of shining green brick and barred windows built between the massive cyclopean columns. But the oddest architectural feature was the little curved towers and pinnacles, with outlines suggestive of leaping flames, that rose from each wall. The rooftops had curved and crooked eaves, giving it a look something like that of a Viking longhouse, or a Chinese pagoda. I looked up, and saw something suggestive in the black sun hanging directly overhead. If there had been a light burning under the silent house, and a vast ceiling above it, it would have cast a shadow shaped something like the disk overhead, and all the flame-shaped pinnacles and eaves would have cast the flaming corona. The doors of the house were barred and locked, and every window as well. Uj was sitting on the doorstep of the house. The front door was a low arch, and a heavy roof, held up by thick posts, formed the porch, and continued upward to form the second floor, that overhung the first. The whole porch was countersunk into the façade of the house, so that to enter the main doors, one had to pass through what was like a low-roofed tunnel. It was cold, bitterly cold here, and my lungs heaved but drew no breath. Almost without thinking, I rotated into being around me the arms and armor I remember from my life as Ydmos. The Living Steel clasped by chest; the gray cloak emitted heat; I took up the cup from my pouch and held it over my mouth and nose, and the substance of the metal in the cup somehow brought fresh air to me. In my other hand, I found the Diskos, that terrible weapon. The disk-shaped blade was motionless, but, beneath my gauntlet, the haft of the weapon tingled and throbbed. There was something achingly familiar about it; a sense of ferocious loyalty. Pepper? Could a futuristic weapon be haunted by the faithful ghost of a long-dead hound? The idea was silly, and yet … Uj was seated as I have seen Tibetans sit, with his heels on the ground and his rump resting on his ankles. He was dressed in his wolf-skins. In one paw was his bone truncheon; in his other, was a fist-sized statuette of a big-bosomed and pregnant woman, very crudely carved. Uj was rubbing the big belly of the mother-stone with his thumb, and crooning to himself, a sad little song. I stepped toward him. “Where is this place?” He looked up. “This-“ he gestured toward the outer gloom of blood-colored light. “This is the scaffolding of the new universe.” “We are not in the universe?” “No. There must be some outside place for the scaffold to stand.” “And this house?” “This is the House of Silence. In your era, it stands in the west of Ireland lies, near a village called Kraighten. It is swallowed by the Earth, so that, in the time of Ydmos, it will be present when the earth is shattered to her core. There will be a great valley, warmed by the last ember of dying geothermal heat, where the Last Redoubt rises; and the House of Silence stands on a small hill to the north. Their poets say the doors of this house have never been closed since all eternity: but there are many time, years and centuries at a time, when the doors close and nothing from the Night World enters the three dimensions occupied by man. Each time, the doors open for you.” “What is in this house? Inside it?” “Everything. The seed of all time and space is within, waiting to begin its growth. And waiting outside …” He made a gesture, pointing to the slopes. At first, I thought they were statues, sphinxes built of an unimaginable scale. I could not calculate the size; they were on the slopes of the mountains surrounding the crater, and so must have been hundreds or thousands of miles away from me. Something as far off as the Moon is visible to the naked eye, but only if it is as large as the Moon. Every few miles, peering from behind the Everest-sized hills and hillocks of those endless, immense slopes that surrounded the crater, were vast and inhuman faces, staring eyes. Godlike visages, you could call them, but only if gods were bent utterly on cruel and dark and inhuman purposes. One of them had the head of a jackal; another wore a necklace of skulls, and held up many weapons in many arms. Others looked like the monsters and grotesques from Polynesian totems, or the squat and ugly carvings from buried Aztec temples. But no, they were not statues. A sense of horrid and infinite life radiated from each of them: if life could exist without Time. I said, “They are waiting to enter in. I will not open the door for them.” He shook his head, and showed his fangs: an expression of sardonic pity. “I have said before: you are not the one who opens it. It cannot be opened from this side. It is opened for you.” I heard, very softly, a footstep behind the door, as if some slight figure were coming down the stairs to a main hall, approaching. A woman’s footstep. I remembered the horrid image of the iron space-ship hull, surrounding me, closing in. I thought once again of what a two-dimensional man, living in the surface of a balloon, might see, how it might look to him, if the balloon were turned inside-out. I said, “If this house is larger on the inside, then, no matter what this seems to look like, these-these giant blocks--these are the inner walls. This endless plain out here is not the outside. It is the inside, a tomb, perhaps, or a prison-cell.” He pointed with his bone truncheon. In the far distance, with no noise at all, the jackal-headed giant, taller than the tallest mountain of earth, had risen to its monstrous feet. The other huge and terrible figures were still recumbent. I cannot express how inhuman, even now, when one of them had moved, was the sense of the pressure of eternity here: the utter, absolute stillness of the watchers was oppressive, like staring at the dark place between the stars on a moonless night, and realizing your eyes were showing you a night with no further shore to it, an abyss without bounds. If that abyss could turn and look at you, it would wear such as face as these watching things. He said, “These are gods. Who could imprison them?” I said, “There must be a way out of this trap. There must be.” “No. Even if you kill yourself, you only end up back here. This is where those who kill themselves are sent.” Interesting. I pointed at the hideous outer gods watching us with unblinking eyes from the vast slopes of the red-lit crater walls. “Then, did they kill themselves?” “They destroyed the first universe, and themselves, because they hated it. Call that rebellion, if you wish, but it is something far worse. It is the malice that is utterly selfless, willing to die, merely so that the object of your malice might suffer.” I remembered what Lisa said about the insult to all life a suicide committed. “Life threw them out of her house.” “You think it is a punishment? A river is not punished for falling downhill to merge and be swallowed by the sea.” I said, “And you and I are here because…” “We let them touch us. When you were Enoch. When I was Krag. We wanted eternity, for ourselves, and our loves. We stepped outside of time, and they were waiting there. You say there is a way out of the trap? This trap is the size of the universe. And your lover is behind the door, and she will open it for you.” There was a noise from behind the low, thick door to the House. A scrape of metal; as if someone were fumbling with the key. I looked out at the giants, the fallen gods, the creatures of darkness, larger than mountains. In the remote distance, the jackal-headed god had raised his hand. A company of abhuman creatures, swine-headed and loathsome to the eye, came trotting around the wing of the House. They walked on two feet, like men, and carried axes and maces in their paws. When the leader of the band saw me, it threw back its snout and gave a high-pitched squeal of rage and hate. The other abhumans snorted and grunted with pleasure and bloodlust, and the ground broke into a run, coming for the stairs to the porch. I put the Diskos to one side. It stood upright, hovering a half-inch off the ground, waiting. I rotated my other weapon into being in my hands, raised my trusty Holland and Holland rifle, took aim at the leader of the swine-things, and shot. I shot and killed two more before they were upon me. Ammo gone, I dropped the rifle. The Diskos jumped back into my hands; I swung the mighty weapons and tore a swine-creature in half. Lightening sizzled from the blade, jarring and shocking any swine-men touching the one I bisected. Bloodstains were on the ceiling above me: I swung the pole-arm left and right, chopping off limbs and heads… I was knocked from my feet. A swine-man broke his dagger against the stubborn armor of my chest; but the stink of his breath was in my nostrils; I could see the tiny hairs of his bristles around his white eyes, the fluid down the twin tubes of his ugly nose, the foam on his tusks… The door behind me shivered in its frame. A crack of light appeared, running from the top of the doorframe to the threshold. A low, thin, piercing cry (which I heard even above the roar of my disk-weapon, above the hideous pig-squealing of the abhumans) echoed from the distant Watchers. They had waited an eternity. They had waited for an entire universe to grow old and die. They had waited for this moment. Two of the swine-men wrestled the Diskos from my grasp. The weapon shocked them, and they fell, their paws burnt and bloody from where they had touched the haft. The memories of Ydmos stirred in my memory: and I wondered where the charge of Earth-Current the weapon was using had come from. Something else from Ydmos stirred in my memory as well. His people knew the art of resisting mental domination. It had not worked perfectly, and the enemy could find ways around it, as it had with him, for the enemy had found a way to drive him mad, and have his kill his own loved ones. But, he still knew enough to know how false memories could be implanted. I remembered the Irish Elk. I remembered what he great and magnificent beasts had looked like, rushing along the grassy plains which, at that time, stretched across all Europe, including the peninsula that one day, half-submerged, would be the British Isles. There was a lie in my memory. How had I not seen it before? He-Sings-Death was a cave-man, from some fourteen thousand years before Christ. Enoch was a Biblical antediluvian. The ages of the Biblical patriarchs, when added up, did not reach back farther than 4000 or 5000 years at most: less than half the time. Uj was a Neanderthal Man. His race dates from two hundred thousand years before Christ. The Neanderthal came from world that the Nephilim, the sons of Cain, could not come from. These outer beings were not fallen angels. They were not the devils from the mother’s Bible lore, any more than they were the Dry Folk of The Smotherer that He-Sings-Death took them to be. It was a lie. The memories in my head of Enoch, son of Cain were in invention. I had never made a bargain with the Dark Powers. I had never bowed down to them, not in any life. My soul was not entangled with them. I rotated the thousand-sized figure in my mind, and, at once, the false memories of Enoch were gone. Whatever happened now, they could not follow me through my own soul. The worm had wiggled off the hook. Even with half a dozen of the squealing, stinking, pig-things on me, I reached out my hand. Ydmos did not know how the Diskos was magnetically attuned to the soul of the user. The science, by his time, had been forgotten. But Abraxander-the-Threshold knew it. A slight push in my imagination on the thousand-sized figure, and the mighty weapon popped into and out of the fourth dimension and it was in my hand again. Ydmos did not know how the spiritual energies in the weapon were programmed. He did not even know what the weapon was made of. But the Blue Man knew. I knew. The slightest touch on the thousand-sized figure brought the blue assemblers into my bloodstream, my skin, my nervous system. My skin turned blue. I had no need for the two systems to “handshake”, since the Diskos was already attuned to me. As quickly as that, and I had a mental link with the spirit in the weapon; and I knew the programming codes. The safety interlock disengaged. Ydmos had not even known there was a safety interlock. I programmed the weapon to do what it was that the arrows of Mneseus had done, but, with the core of power in the haft of the weapon, there was tremendously more force than a spark rubbed from amber could summon. Then, mentally, I order the power core to overload. White fire shined from the weapon, and flashes of terrible lighting shot in each direction. My armor grounded me, but not the swine-things touching me. The electricity flowed to them and to their comrades touching them. The whole huddle of the creatures was paralyzed as their limbs jerked with torture-spasms. I stood, and threw the whole lot of them from me. The one or two not already dead, I decapitated with a backhand stroke of the mighty weapon. Sparks and black smoke poured from the piled corpses around me. He-Sings-Death had not known why the after-life creatures, the monster he had thought was the King of the Dead had allowed him to see the ghost of his wife in a dream, but Ydmos understood the aetheric energies involved in connecting the living and the dead. Mneseus understood necromancy. He-Sings-Death thought that the horror he had met, had begged, and had sung his sad songs to, had been moved by his plea to allow his wife to live again. All a deception. All a lie. The death-being had been used that sorrow, that plea, and those tears to make a connection similar to the connections I was using to call weapons into my hands from across the barriers of time and space. He-Sings-Death had been allowed to go down into the underworld and returned, not to bring his wife to life again, but to let the horrors who fed off the souls of the dead following him back up to the light again. That was why he had been told not to turn his head; so that he would not see what was following him. Poor fool. He had opened the door for them. But who could close it again, once opened? The swine-things were slain or thrown back, but, at that same moment, like a mist rising from the ground, I saw dozens of pale and terrible spirits, hooded and shrouded in gray, and silent as death itself, standing before me. I heard the door-hinges creek behind me, and the door swung open. I backed up, and took my position in the threshold. She was behind me, as I knew she would be. Uj, I did not see him; I hope he scuttled inside during the confusion. Even him, I would not leave out there, in the airless red plain of silence, with them. The silent, robed figures raised their left hands, all in unison. The open doors turned into green jade, and the stones of the porch and threshold melded or bonded with them in a strange fashion I did not comprehend. The door now could not be shut. All the silent, huge and misshapen outer gods rose to their feet, sending the mountains tumbling.

33. THE MASTER OF THE MASTER-WORDOne of the hooded figures glanced at me, and my heart burned with cold in my chest, so painfully that I would have dropped my weapon, if my weapon were not, of its own accord, holding itself in my hand. Faint, I would have stumbled and knelt, had not the soft hands behind me, woman’s hands, held onto my gray cloak. I leaned heavily on the shaft of my weapon, and she prevented me from falling. I said, “Why didn’t you leave me out here?” From behind me, I felt her warm breath tickling my ear. “Don’t be silly. Say the word.” She was using the language of Ydmos’ time. It was the Inner Speech, the tongue he had never thought to hear again. And the declension using in that strange language was not the mode used when a grave danger threatened. It was the mode used only during decontamination procedures. Her voice was rich with unspoken laughter. At the very moment of the utter and absolute victory of darkness, she was amused at them, as if they were harmless: a mere after-thought, a fading nightmare, which the new universe would soon forget. The word she meant, of course, was the Master-Word. I said, “What? The Master-Word won’t drive them away. It has no power over them. It is merely something they cannot say.” The hooded shapes were on the porch now, standing silently. I had not seen them move. A terrible cold, a sense of airless vacuum, came from them. She said, “A dog hair cannot bite someone, but you called Pepper from outside of time. You called Africa to you, and me. Why not more? There is One who is out there, who can do more than Pepper can.” “What One? Who?” “The One who promises that all lovers will be reunited after the end.” I said the master-word. She was right. I could sense or see links, like the same chain that bound my soul to hers, running from the master-word to some ulterior power beyond all space and time, deeper than the foundations of the universe. With the slightest rotation of the thousand-sided, nine-dimensional solid, I called the One, whoever or whatever He was, that had first spoken that word into being, and invited Him to enter this scene, this universe, and my life. The light was too bright to look at, but, once I got used to it, I saw her, and I turned, and I embraced her, despite the hardness of my armor. The door closed behind me.

It was so bright within.

© John C Wright 1 Nov 2003

|